By Martin Cole-

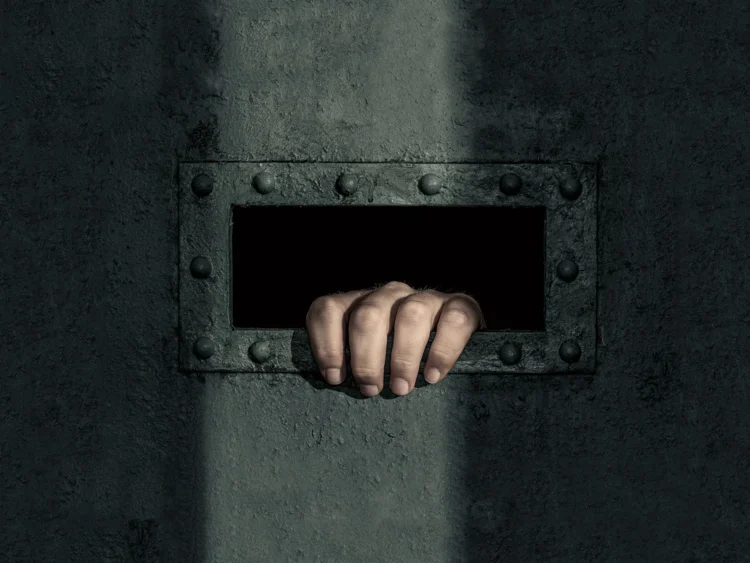

A 13-year-old Indigenous Australian boy spent 45 days in solitary confinement while being held for minor offences, in the latest youth justice case to raise human rights concerns in Queensland.

The boy , referred to as “Jack” – was released on probation last week after 60 days in custody at Cleveland Youth Detention Centre in Townsville.

The human rights chief in Queensland says the case may have broken state laws.

The young lad who has no criminal record was being held on remand on charges relating to a fight with another 13-year-old boy, at the detention centre some 1,300km north of Brisbane.

He was initially arrested in October 2022 in relation to a fight with another boy.

In January 2023, the boy was arrested for further offences, including property offences and attempted unauthorised use of a motor vehicle.

He was formally reprimanded in the children’s court last week, with his probation order extended by a month. During an initial 14-day period at Cleveland, from 27 October to 10 November, the boy was confined entirely to his cell.

The court has not published a judgment in relation to the boy’s case. But in several recent cases, the courts have raised concerns about the treatment of children and warned that prison conditions would heighten the risk of reoffending.

The boy is understood to have been denied drinking water at the Cleveland Youth Detention Centre in Townsville, Queensland (CYDC), after he became distressed during a prolonged period in isolation and flooded the cell.

He was released after being formally reprimanded in the children’s court last week, with his probation order extended by a month.

The boy’s treatment in the facility was shameful and is considered the most extreme of several recent cases

Describing his detention as “extraordinary and cruel”, Mr Grau said Jack had “no serious criminal history”.

“He was 13, he’d been in court once before. So even for this offending, he was never going to get a period of incarceration, in my view,” he said.

Mr Grau said he didn’t know why Jack spent so long in isolation, but suspected it was due to staff shortages at the prison.

“If he’s being locked in because there’s staff shortages, and Cleveland detention centre has 80 or more kids in at any one time, one can only assume that other kids are in the same circumstance.

“You would hope not, but maybe it’s more common than we thought.”

Jack’s period of detention included six days being held in adult prisons. He was released last week with a verbal reprimand.

The situation raises human rights concerns over the Queensland’s youth justice system, which is currently undergoing reform.

In February, it emerged that another 13-year-old Queensland boy with developmental disabilities spent 78 days confined to a cell for 20 hours per day.

Queensland is currently debating new laws which would criminalise bail breaches by minors – a change which will cause the youth prison population to increase dramatically, experts warn.

State Human Rights Commissioner Scott McDougall said the recent cases may have breached Queensland’s Human Rights Act, which states all prisoners should have access to fresh air and exercise for a minimum of two hours a day.

He warned that changes to the law would worsen the situation as he called for urgent steps were needed to stop children being placed in isolation.

Mr McDougall called for the state government to “double down” on measures to keep children in school and stop them going down “the path of criminalisation”.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were 12 times more likely to be in prison than non-Indigenous Australians in 2021, the Queensland Statisticians Office says.

Indigenous children account for some 70% of detainees across most of Queensland, and over 90% in the state’s north.

Queensland boy, 13, spends at least 45 days in solitary confinement despite not being sentenced to detention

Youth detention centres are already at capacity and large numbers of children – at one point, more than 80 – are being warehoused in adult police watch houses. The Cleveland youth detention centre has also been subject to chronic staff shortages, resulting in prolonged “blackout” periods where children are not allowed to leave their cells.

Most children imprisoned in the Queensland youth justice system are on remand. Those numbers have increased significantly since the introduction of 2019 bail laws, which reversed the presumption in favour of bail in cases where there is an “unacceptable risk” to community safety.

In practice, that has meant dozens of children have been sent to prison – unsentenced – in cases where their alleged offending was not serious enough to warrant a period of imprisonment at sentence.

In the case of the 13-year-old boy, he was initially arrested in October 2022 in relation to a fight with another boy.

In January 2023, the boy was arrested for further offences, including property offences and attempted unauthorised use of a motor vehicle.

He was formally reprimanded in the children’s court last week, with his probation order extended by a month.

During an initial 14-day period at Cleveland, from 27 October to 10 November, the boy was confined entirely to his cell.

From 30 January to 6 March, the boy was imprisoned at Cleveland and only allowed out of his cell on five days. He was in solitary confinement in his cell from 1 February to 23 February.

Information about his imprisonment at the detention centre does not include details about his final four days, from 7 to 10 March.

The court has not published a judgment in relation to the boy’s case. But in several recent cases, the courts have raised concerns about the treatment of children and warned that prison conditions would heighten the risk of reoffending.

Judge Tracy Fantin published a judgment last month relating to another 13-year-old boy – who has developmental disorders – who spent extended periods in solitary confinement.

Fantin said the circumstances of the child’s imprisonment breached several principles of the state’s Youth Justice Act. The judge also drew clear links between the treatment of children in prison and the likelihood they would reoffend.

She said the boy’s period in detention “will have achieved little or nothing to protect the community from … future offending”.

“Indeed, it may well have increased the risk of further offending … and the state of Queensland must bear responsibility for that.

“If you treat a child like an animal, it is unsurprising that they may behave like an animal.”