By Tony O’Reilly And Emily Caulkett-

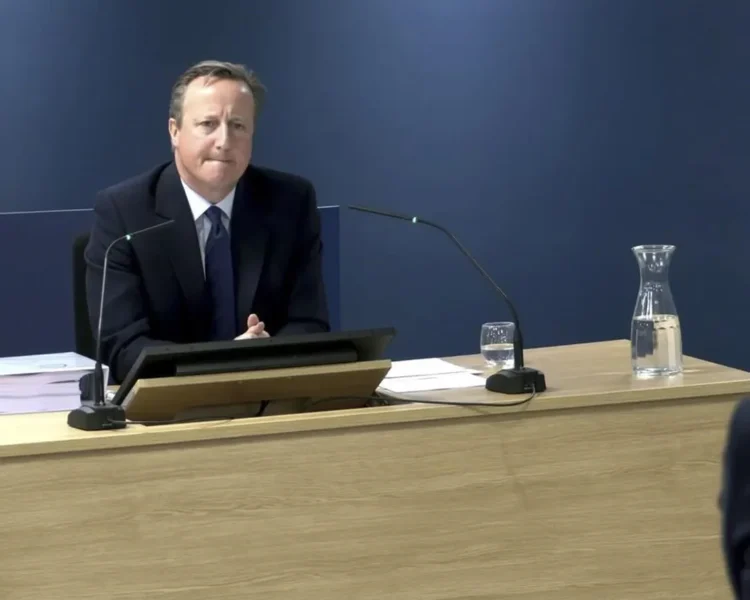

David Cameron admitted failing in preparing for pandemic, as he was grilled for over two hours by the Covid inquiry about preparation under his administration for the pandemic.

Cameron who was prime minister of the Uk between 2010 and 2016 was heckled with shouts of shame on you, as he left the hearing in London, after shouts of ‘scum. scum’as he arrived in London for the inquiry.

Mr Cameron finished his evidence by saying he was “desperately sorry about the loss of life” in the UK during the pandemic.

Giving evidence to the Covid Inquiry, Mr Cameron said “group think” meant his government did not focus enough on pandemics other than flu.

“The failing was not to ask more questions about asymptomatic transmission,” he added.

Asked about Dame Deirdre Hine’s independent review into swine flu, he said: “My reaction to reading Hine was, like many of the other reports, it doesn’t mention the potential for asymptomatic transmission.

“And so, you know, when you think what would be different if more time had been spent on a highly infectious, asymptomatic pandemic, different recommendations would have been made about what was necessary to prepare for that.”

He also denied that his government’s austerity policies damaged the UK’s ability to cope with Covid.

The inquiry is currently considering preparedness ahead of the pandemic.

George Osborne and Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor and health secretary under Mr Cameron, will give evidence to the inquiry later this week.

Questioned by the inquiry’s lawyer Kate Blackwell KC, Mr Cameron said: “Much more time was spent on pandemic flu and the dangers of pandemic flu rather than on potential pandemics of other, more respiratory diseases, like Covid turned out to be.

“This is so important – so many consequences followed from that.”

“I’ve tried to be as frank as I can and as open as I can about the things my government did that helped… but I’ve also tried to be frank about the things that were missed,” he told the inquiry.

In response to whether he accepted health budgets during his time in office were ‘inadequate’ and led to a ‘depletion’ in NHS services, the ex-PM said: ‘I don’t accept that.

He added: ‘I don’t think you can separate the decision and the necessity of getting the budget deficit down, and having a reasonable debt to GDP ratio, so you can cope with future crises – I don’t think you can separate that from the funding of the health service or, indeed, anything else.

‘If you lose control of your debt and you lose control of your deficit and you lose control of your economy, you end up cutting the health service.

‘That’s what happened in Greece, that’s what happened in countries that did lose control of their finances.

‘We made the important decision to say the health service is different, its budget would be protected, so there were real-terms increases every year.

‘So, for instance, there were 10,000 more doctors working in the NHS at the end of the time I was PM than there were at the beginning.

‘Would everyone like to spend even more on the health service? Yes. Making these difficult choices about spending, it wasn’t an option that was picked out of thin air.

‘I believed and I still believe it was absolutely essential to get the British economy and the British public finances back to health so you can cope with a future crisis.

Significant

David Cameron’s appearance before the COVID-19 inquiry holds significant implications because he was responsible for the country’s governance during a period preceding the pandemic.

The pandemic preparedness was a complex and multifaceted task that extends beyond a single administration. Governments must continuously evaluate and adapt their strategies based on evolving scientific knowledge and global health risks.

Foreseeing the exact occurrence of a specific pandemic is an immensely challenging task. While public health experts and organizations have long highlighted the threat of global infectious diseases, predicting the exact timing and nature of an outbreak is near impossible.

Governments typically rely on expert advice and scientific research to shape their strategies, yet all responsible governments are expected to have sensible frameworks in place for such possibility, and conduct their administration in a manner that makes adaptability to pandemics not very difficult.

However, the government has always been well aware of the spread of viruses, making the possibility of a pandemic not a farfeched one.

The extent to which Cameron’s decisions or policies may have contributed to any deficiencies in preparedness will be the legitimate subject of discourse.

The inquiry is expected to consider the collective efforts of multiple administrations, the influence of international organizations, and the challenges posed by an unprecedented global crisis. The focus should shift toward identifying the lessons learned and implementing reforms to strengthen future pandemic preparedness.

The ultimate goal should be to learn from the experiences of the past and strengthen the country’s ability to respond to future health crises.

The inquiry, which is set to last until 2026, is in its second week.

George Osborne, who was chancellor in Mr Cameron’s government, will give evidence on Tuesday.

Mr Cameron was asked whether health inequalities increased during his time in office. He said the figures didn’t necessarily back the idea that austerity was to blame.

His critics have argued his government’s policies decimated the national health services.

The unions federation said the ex-prime minister and George Osbourne, the chancellor at the time (who is testifying tomorrow), ignored warnings about the impact of austerity on the UK’s preparedness, and instead “pushed millions into poverty”.

“We had some very difficult winters with very bad flu pandemics; I think that had an effect. We had the effect that the improvements in cardiovascular disease, the big benefits that already come through before that period, and that was tailing off,” Mr Cameron told the inquiry.

“And then you’ve got the evidence from other countries. I mean, Greece and Spain had far more austerity, brutal cuts, and yet their life expectancy went up. So I don’t think it follows.”

The former prime minister added that child poverty, and the number of people, including the number of pensioners, living in poverty all “went down” and insisted that many of his government’s policies were about “lifting people out of poverty”.

Cameron denied he left the government unprepared when he stepped down from office in 2016, but he did say it was a “mistake not to look more at the range of different types of pandemic”.

He pointed to the National Risk Register and the National Security Secretariat.

“We did more than many to try and scan the horizon, to try and plan. We did act on Ebola, we did carry out these exercises, we did try to change some of the international dynamics of these things,” he said.

Image:PA