Tony O’Reilly-

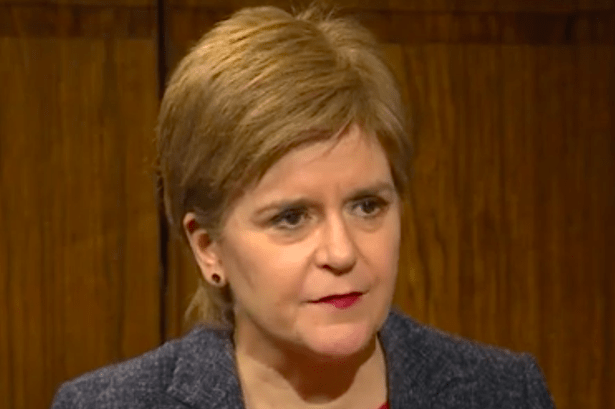

Scotland’s first minister Nicolai Sturgeon has threatened to take the British government to court over its decision to block a Scottish law that makes it easier for people to change their gender on official documents.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said the Conservative U.K. government was making a “profound mistake” by vetoing the Gender Recognition Reform Bill passed by the Scottish parliament last month.

The bill would allow people aged 16 or older in Scotland to change the gender designation on their identity documents by self-declaration, removing the need for a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria.

The bill was also established to cut the time trans people must live in a different expressed gender before the change is legally recognized, from two years to three months for adults and to six months for people ages 16 and 17.

Scottish Secretary, Alistair Jack, told MPs he was making a so-called section 35 order under the 1998 Scotland Act, which created the devolved parliament, which meant the gender recognition reform Scotland bill would not receive royal assent.

Welsh first minister, Mark Drakeford, said the decision to use a section 35 order marked “a very dangerous moment”, adding: “I agree with the first minister of Scotland that this could be a very slippery slope indeed.”

The debates took place before most MPs had been able read the “statement of reasons” in which the UK government set out its legal basis for imposing section 35, which was published nearly two hours after Jack’s announcement.

Scotland’s social justice minister, Shona Robison, told MSPs in response to an urgent question in Holrood that the order represented “a pattern of behaviour” of attacks on devolution by the UK government.

Robison said: “I want to be very clear to all trans people that I know will be incredibly upset by this decision: this government will seek to uphold the democratic will of this parliament

The contested Bill makes amendments to the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (the 2004 Act) for Scotland, significantly altering how applicants can be issued with a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC) under Scots law. People can apply if they are the subject of a Scottish birth register entry or if they are ordinarily resident in Scotland.

The amendments made by the Bill to the 2004 Act will make it quicker and easier for Scottish applicants to obtain a full GRC, removing a number of measures which the UK government regards as important safeguards, including the removal of the requirement for an applicant to have or have had a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (and, correspondingly, the removal of the requirement for an applicant to provide medical reports with their application)

a reduction in the minimum age for applicants from 18 to 16.

It also includes a reduction in the period for which an applicant must have lived in their acquired gender before submitting an application, from 2 years to 3 months (or 6 months for applicants aged under 18), alongside the introduction of a mandatory 3 month reflection period

The removal of the requirement for an applicant to provide any evidence that they have lived in their acquired gender when submitting an application

the removal of the requirement for a Panel to be satisfied that the applicant meets the criteria, with applications instead being made to the Registrar General for Scotland.

Taken together, these amendments remove any requirement for third party verification or evidence from the process.

The Bill also amends provisions for the process by which people from overseas can obtain a GRC under Scots law. Section 1(1)(b) of the 2004 Act provides for a simpler overseas track enabling a person to apply for a GRC if their acquired gender has been legally recognised in an approved country or territory. Instead, the Bill provides that where a person has obtained “overseas gender recognition”, the person is to be automatically treated as if the person had been issued with a full GRC by the Registrar General for Scotland, unless it is manifestly contrary to public policy.

This provision does not apply to people with GRCs issued in the rest of the UK under the 2004 Act, because section 8M provides separately that they are treated as though they are full GRCs issued by the Registrar General.

The Bill has an exception for circumstances in which it would be manifestly contrary to public policy to do so (for example, in a case where legal gender recognition was obtained overseas at a very young age), although the Bill does not otherwise define when this exception will apply.

The Bill will make modifications of the law as it applies to the reserved matters. Sections 2-6 and 16 of the Bill make modifications to the 2004 Act by repealing ss.1-8 (except s.4(4)) of the 2004 Act and replacing them with ss.8A to 8E; section 8 inserts a new section 8M; section 16 also amends s.25 (which contains the relevant definitions) of the 2004 Act. The Bill therefore modifies the 2004 Act.

The reserved matter to which that law applies is (at least primarily) “equal opportunities”.[footnote 1] The reserved matter is defined specifically as meaning “the prevention, elimination or regulation of discrimination between persons on grounds of sex or marital status, on racial grounds, or on grounds of disability, age, sexual orientation, language or social origin, or of other personal attributes, including beliefs or opinions, such as religious beliefs or political opinions.”

The modified law (the 2004 Act) applies to the reserved matter (equal opportunities) through its inter-relationship with the Equality Act 2010 (the 2010 Act). The 2010 Act provides Great Britain’s legal framework to protect the rights of individuals and advance equality of opportunity for all.

The 2010 Act makes “sex” a protected characteristic and makes provisions about when conduct relating to that protected characteristic is unlawful. Section 9 of the 2004 Act provides that unless exceptions apply, the effect of a full GRC is that “for all purposes” the person’s sex becomes as certified. As a matter of general principle, a full GRC has the effect of changing the sex that a person has as a protected characteristic for the purposes of the 2010 Act.[footnote 2] This is subject to a contrary intention being established in relation to the interpretation of particular provisions of the 2010 Act.

The 2010 Act as a whole was carefully drafted in the light of, and reflecting, the specific limits of the 2004 Act and the relative difficulty with which a person could legally change their sex “for all purposes” (per s.9), including under the 2010 Act itself. The Bill alters that careful balance.

The Bill also has practical consequences on the operation of the law in relation to fiscal and social security

The Secretary of State believes that the modifications to the 2004 Act as it applies to reserved matters would have an adverse effect on the operation of the law as it applies to reserved matters.

Removing safeguards could affect safety in particular that of women and girls, given the significantly increased potential for fraudulent applications to be successful.

The impacts on the operation of the Equality Act 2010 that result from the fact that a GRC changes a person’s protected characteristic of sex for the purposes of the 2010 Act , and the expansion of the cohort of people able to obtain a GRC. This includes (a) the exacerbation of issues that already exist under the current GRC regime.