By Gabriel Princewill-

Victims of Grenfell fire are being cheated of justice in a manner that must question our evaluation of the British justice system.

The deep grievances expressed by the bereaved who lost relatives as a result of the abysmal recklessness of those who were expected to safeguard their interest will remain until they receive concrete assurance that a definite and completely acceptable action is taken without further, undue delay.

The agitation for proper accountability of those responsible for the mass deaths of innocent people gruesomely snuffed out whilst residing in their own abodes is not only perfectly understandable, it is inevitable. Multiple death caused by a fundamental negligence that was preventable is too painful to bare for those who lost loved ones.

Prosecutors have been indecisive as to whether to prosecute the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea owned Grenfell Tower for corporate manslaughter, given its oversight of the disastrous refurbishment programme. There are also other parties whose actions or omissions have made them complicit in the disaster that ensued that fateful night in 2017.

One of the reasons for its indecision has been the fact the council outsourced the job of managing council properties to an “arms-length” body, the tenant management organization (TMO), which was responsible for the long-term safety of Grenfell. The TMO has also been under investigation for corporate manslaughter, but the investigation has yielded nothing.

The TMO is a company limited by guarantee, incorporated on 20 April 1995. On 28 February

1996 RBKC entered into a Management Agreement with the TMO, under which it appointed the TMO to carry out certain housing management functions.

An initial report about the Grenfell fire revealed that floors 4 to 23 of the building were designed to accommodate residential flats, with six flats on each floor. Separating each flat at these levels are reinforced concrete cross-walls.

The report states that the lower levels of the building were designed to provide more flexible community spaces, which subsequently accommodated a nursery, offices and a community health centre on the ground floor and

Yet, the council has conceded to the public inquiry that its building control department didn’t properly check that the refurbishment of Grenfell was safe, and that council inspectors didn’t ask for comprehensive plans for the cladding system and didn’t know what insulation panels would be used, but still signed off the completed work.

The pertinent question is therefore whether the competent building control department of a council would have been expected to be cognizant of the requisite standards for adequate insulation panels or not.

Civil servant, Brian Martins, Head of Technical Policy for Building Regulation, is already on record admitting he could have potentially prevented the Grenfell Tower fire on a number of occasions. So why didn’t he?

Mr Martin had been responsible for official building regulations guidance

Mr Martin had been responsible for official building regulations guidance on fire safety for almost 18 years by the time of the Grenfell Tower fire.

In response to questions of about the incident, he confirmed he was the official with the greatest “breadth and depth of knowledge on the building regulations and guidance so far as it related to fire safety” and the person “to whom others would turn” to answer questions on the topic.

The inquiry has already heard about many critical warnings regarding the looming danger of a cladding fire which were issued to him in this role.

Mr. Martins described the cladding as “very low tech” and “obviously something that was likely to become involved in a fire and result in fire spread”. If you’ve ever repaired a car or perhaps made a canoe in the Scouts with fibreglass, that’s essentially the material they were using,” he said.

Assessment

How then does one couch the overall conduct of the council in the context of accountability and potential charges of manslaughter? The legal test is unarguably prescriptive, not descriptive. In other words, the object of legal inquiry is whether the council’s building department knew or ought to have known that by not ensuring the refurbishment of Grenfell was safe, it was predisposing the residents there to the risk of death in the event of a fire.

An affirmative response is unambiguously tantamount to manslaughter in legal terms, provided the resulting damage from the associated negligent cause of the deaths is not too remote a consequence of the council’s breach of duty. It means factual causation has been established, but even with factual causation, the issue of remoteness can be tricky. Damage which is too remote is not recoverable even if there is a factual link between the breach of contract or duty and the loss.

The loss must be foreseeable not merely as being possible, but as being not unlikely. The knowledge that is taken into account when assessing what is in the contemplation of the parties comes under two limbs: The knowledge of what happens “in the ordinary course of things”, which is imputed to the parties whether or not they knew it is one of the factors considered.

Involuntary manslaughter refers to unintentional homicide from criminally negligent or reckless conduct. The same principle applies to Mr. Martins.

Admissions that he failed to take reasonable steps that could have prevented a fire from spreading in the manner it did and killing multiple victims, makes him a culpable party in the tragic deaths.

The upshot of the matter is that once it is evident that in the absence of the prohibited negligence in question, the eventual damage that occurred would have been avoided, causation is invariably established. Only one discernible complication can rear its ugly head for untangling in the ugly web of events that culminated in the grotesque nightmare that eventuated .

That is fact that the cigarette which was carelessly lit by a resident on the first floor and started the fire was not the doing of any of the negligent parties against which the bereaved families are calling for justice. This fact does not change the relative culpability of any of the guilty parties because indirect causation no matter how remote is still causation.

The fact there are still tens of thousands of leaseholders residing in apartments blighted by fire safety defects similar to those found at Grenfell, and 111 high-rise buildings found to be wrapped in similar aluminium composite cladding to that which was the main cause of fire spread at Grenfell have not yet been fully fixed, is extremely alarming. It reflects an indifference for the safety of those who reside in those apartments.

Justice

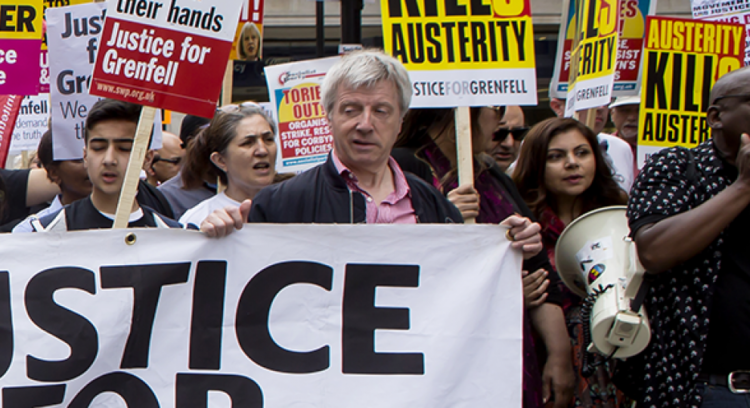

It is no wonder the bereaved families are so disgusted by it all that they continue to push for justice. On top of the deep grief and sense of loss, they feel denied of justice, which is meant to be for all. They have spoken of having to knock on people’s doors loud enough to get their voices heard. The Metropolitan police will not decide on whether to recommend criminal charges until after the inquiry publishes its final report, which is not likely to be until 2023.

So far, the force has made one arrest, on suspicion of perverting the course of justice, and carried out several interviews under caution for suspected gross negligence manslaughter, corporate manslaughter, fraud, and health and safety offences. Yet, the simple fact is that the justice system is painfully failing all the victims of this tragedy.

When The Eye Of Media asked the Met police spokesperson on Tuesday evening to put its generic press release to one side and answer the simple question of whether given all the facts at its disposal, it was not ascertainable whether any parties were legally guilty of manslaughter, their spokesperson skirted the question and simply said ”all we can say is there is an ongoing investigation and we can’t comment any further beside the press statement we have given”. Perhaps the Met are themselves grappling with the legal issues, but not for this long.

One clear logical inference is that anybody whose action or omission constituted a negligence without which the multiple lives lost would have been saved, is guilty of manslaughter.

However, the complication with cases like this is limited to the fact there is a clear absence of intention to kill on the part of the negligent parties, but causative factors in this tragedy are incontrovertible.

Remote causation is established and consequences proportionate to that causation ought to be implemented in a system with a just framework

Scotland Yard has described the investigation as a “large and complex criminal investigation”.

The surviving family members are stuck in the pain of the whole affair.

Karim Mussilhy, whose uncle Hesham Rahman, died in the tower, said: “We are stuck in the same place as five years ago – a feeling of injustice and having to bang on doors to make our voices heard. Are we going to be talking about [whether there will be criminal] charges on the 10th anniversary?”

Edward Daffarn, who escaped the 16th floor, said the country should be ashamed of its response. “My mental wellbeing is very closely linked to justice and feeling that we create some sort of legacy,” he said. “But we haven’t got to that, through no fault of our own but through a mixture of incompetence and indifference from those who actually have the power to make those changes.”

Reforms of landlords’ fire safety duties, including requirements to check fire lifts and ensuring firefighters know about the makeup of buildings’ external walls, will be laid before parliament this coming autumn. Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London, said on Sunday that reform “urgently needed to avoid a similar disaster is not happening fast enough”.

Last week Michael Gove, the secretary of state for levelling up, housing and communities, apologized for the government having been “too slow to act” and having “sometimes behaved insensitively” over the last five years. Apology, though welcome, is inadequate and not good enough.

A spokesperson for his department said the new Building Safety Act “brings forward the biggest improvements in building safety for a generation”, and said 45 housebuilders had now agreed to pay £5bn to fix high-rise buildings found to be unsafe.