By Samantha Jones-

The oldest DNA yet extracted from human remains in Britain or Ireland has revealed that at least two distinct groups with different ancestry migrated to the United Kingdom at the end of the last ice age.

The DNA is from individuals who lived more than 13,500 years ago, and indicates the presence of two distinct groups in Britain at the end of the last Ice Age. Along with other new evidence on their diet and culture, their genetic and cultural diversity paints a more complex picture of the humans that recolonised Britain at the end of the last Ice Age.

Approximately two-thirds of Britain was covered by glaciers during the Ice Age. Around 17,000 years ago, as the climate warmed and the glaciers were melting, drastic ecological and environmental changes took place and humans began to move back into northern Europe. For the first time the study reveals the recolonisation of Britain consisted of at least two groups with distinct origins.

Scientists found that the two groups differed in their rituals and diets, as well as their genetic profiles, at a time of rapid environmental and ecological change.

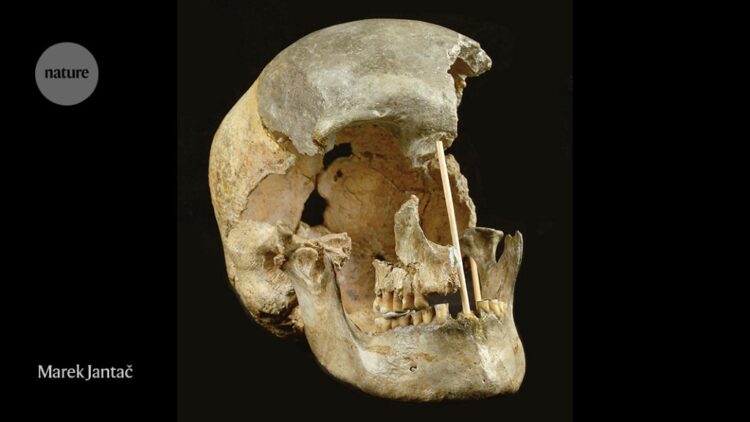

Researchers from the UCL Institute of Archaeology, the Natural History Museum and the Francis Crick Institute looked at the remains of two individuals – a woman from Gough’s Cave in Somerset and a man from Kendrick’s Cave in North Wales – using DNA analysis, radiocarbon dating and the chemical composition of their bones.

The fragments of DNA recovered from the Gough’s Cave female revealed that she came from a group which had made its initial migration into northwest Europe around 16,000 years ago.

The study, published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, said she died about 15,000 years ago.

According to the findings, advances in sequencing technologies combined with improved laboratory methods and bioinformatic workflows have facilitated the analysis of genetic signatures of Late Pleistocene European populations. A number of studies have explored the genetic makeup of the earliest modern humans in Europe, before the emergence of agriculture.

The study also found that these populations were not just genetically different, but culturally different too. ‘Chemical analyses of the bones showed that the individuals from Kendrick’s Cave ate a lot of marine and freshwater foods, including large marine mammals. Humans at Gough’s Cave, however, showed no evidence of eating marine and freshwater foods, and primarily ate terrestrial herbivores such as red deer, bovids (such as wild cattle called aurochs) and horses,’ says Dr Rhiannon Stevens, Associate Professor of Archaeological Science at UCL Institute of Archaeology

Chemical analysis of her bones revealed she probably had a diet based on animals which ate plants, such as red deer, bovid (wild cattle) and horses.

DNA fragments recovered from the man found in Kendrick’s Cave suggested an ancestry from a group of western hunter-gatherers who are thought to have migrated to Britain around 14,000 years ago.

The man lived around 13,500 years ago and had a diet consisting mainly of food from the sea and rivers, including some marine mammals, the researchers found.

Animal and human bones found in the caves also revealed the different customs of the two groups, particularly those relating to death and burials. In recent years, advances in sequencing technologies, combined with improved laboratory methods and bioinformatic workflows, have opened up the possibility to generate and analyse the genetic signatures of Late Pleistocene European populations.

It also revealed that a number of studies have explored the genetic makeup of the earliest modern humans in Europe, before the emergence of agriculture

In Gough’s Cave, some human skulls had been modified into ‘skull-cups’, providing evidence that the site was used for ritualistic cannibalism, according to the study.

In Kendrick’s Cave, only animal bones were found, including items such as a decorated horse jawbone, indicating the cave was likely used as a burial site by the occupiers.

“This is the first ancient DNA from Palaeolithic Britain (Old Stone Age)”, study co-author Rhiannon Stevens, an associate professor at the UCL Institute of Archaeology, told Sky News.

“It shows that we can get useful genetic information from material that comes from Palaeolithic Britain, and in the case of Kendrick’s Cave, material that was excavated in the late 19th century”.

About two-thirds of Britain’s landmass was covered by ice during the Last Glacial Maximum – about 20,000 years ago – and it would have been too cold for humans to live there.

Then, about 19,000 years ago, there was widespread melting of the British-Irish ice sheet.

About 3,000 years later there was virtually no ice left covering England or Wales, at a time when humans could begin to move back into northern Europe.

“This is an important time period for the environment in Britain, as there would have been significant climate warming, increases in the amount of forest, and changes in the type of animals available to hunt”, said co-author Sophy Charlton, a biomolecular archaeologist and postdoctoral researcher at the Natural History Museum.

“Finding the two ancestries so close in time in Britain, only a millennium or so apart, is adding to the emerging picture of Palaeolithic Europe, which is one of a changing and dynamic population”, said co-author Mateja Hajdinjak, a postdoctoral fellow at the Francis Crick Institute.

Gough’s Cave is also the site where Britain’s famous Cheddar Man was discovered in 1903.

Cheddar Man, thought to have lived more than 10,000 years ago, is the earliest known Briton to have mixed ancestry – mostly western hunter-gatherer and some DNA connecting him to the initial migration group.

A study in 2018 of his DNA discovered he had dark skin, blue eyes and black curly hair.

Their mortuary practices also differed. There were no animal bones showing evidence of being eaten by humans found at Kendrick’s Cave, indicating that the cave was used as a burial site by its occupiers. Animal bones that were found included portable art items such as a decorated horse mandible. In contrast, animal and human bones found in Gough’s Cave showed significant human modification including human skulls that have been modified into ‘skull-cups’ and interpreted as evidence for ritualistic cannibalism.

Co-author Selina Brace, a biologist and principal researcher at the Natural History Museum, said: “We really wanted to find out more about who these early populations in Britain might have been.

“We knew from our previous work, including the study of Cheddar Man, that western hunter-gatherers were in Britain by around 10,500 years BP, but we didn’t know when they first arrived in Britain, and whether this was the only population that was present”.

Despite the findings, Stevens urged that caution was “needed as we only have data from two individuals and the archaeological evidence from across northern Europe is also at odds with the over-simplistic correlation of genetic signatures, social groups and archaeological cultures”.